One Year of War - 2022 Recap

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has been ongoing for nearly one full year. As fighting escalates, here's a footnote-heavy recap of the last year and where things stand, intended for all audiences.

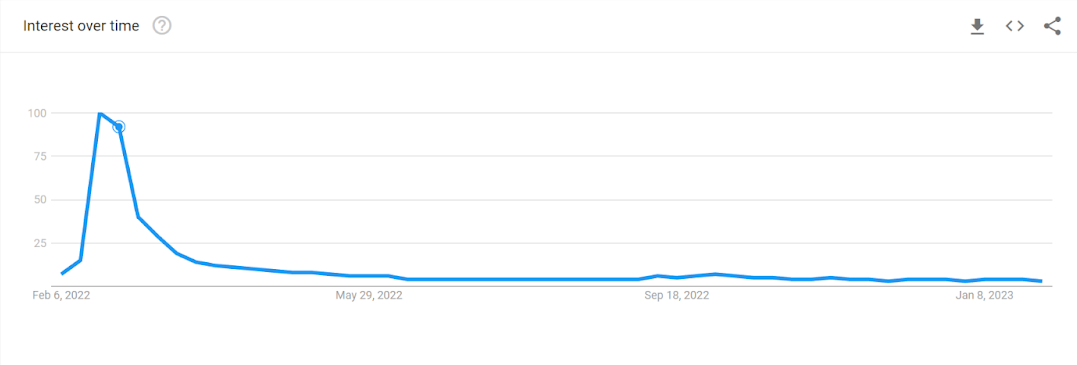

For a few days in February 2022, Ukraine’s courageous and impressively effective stand against the full-scale Russian invasion captivated the world. Media attention focused intensely on the invasion for a couple of weeks; it was seemingly all anyone could talk about. Every company you had ever bought a single product from was sending you unsolicited emails soberly stating that they stand with Ukraine.

As the war progressed, the share of media attention devoted to its coverage dwindled. This was expected, especially as the war settled into a semi-stable1 configuration— but it has meant that it’s fallen off people’s minds (no judgment if it has fallen off yours!) and steadily faded into the background for us in the states, while people have continued to fight and die.

The war won’t end this year, and it may not end next year; Russia is continuing to quietly mobilize tens of thousands of soldiers in preparation for new offensives, and the risk of major international escalation is ever present.

As such, it’s important that we all start on the same page, and I thought it best to write up a footnote-heavy layperson-friendly recap of the conflict so far from January 2022. Don’t fret, though— future posts are not intended to be this long (or to have this many maps with arrows)!

The roots of this war go back to the 2014 Maidan revolution and subsequent Donbas insurgency, and before that to the rule and dissolution of the USSR, the Holodomor, the Russian Empire, and back into the history of the Cossacks, the Crimean Tatars, the ‘Wild Fields,’ and so on. While that history is crucial, fascinating, and worth reading, it’s definitely outside the scope of this post2; the major takeaway is that this conflict did not come out of nowhere and in many ways this last year has only been the largest escalation in a nine-year-old war.

Following two Russian military buildups near Ukraine in spring and fall 2021, multiple denials of intent to invade from Russian officials, and Russian recognition of the LPR and DPR3 as independent states, Russia launched its full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022. The subsequent course of the war can be broken up a variety of ways, but I’ll divide it into four major phases:

Invasion - roughly February to April 2022, until Russian retreat from Kyiv and northern Ukraine

Second phase - Summer 2022, ending before the Ukrainian counteroffensives in Kherson and Kharkiv

Third phase - Fall 2022, beginning with the seizure of initiative4 by the Ukrainians in two counteroffensives, arguably ending with the onset of the muddy season and the culmination5 of Ukrainian offensive operations around the new year.

Fourth phase - February 2023 and beyond. It seems the Russians have the strategic initiative. This will likely be characterized by the most significant offensive operations since February 2022 by one or both sides, but only time will tell.6

The first phase of the war was dramatic, shocking, and widely publicized, so I will be brief. Russia launched strikes across Ukraine overnight on the 23rd of February 2022. After the first hours, it became clear that this was an extremely (and excessively) complex invasion aiming for multiple ambitious objectives: a coup de grace against Kyiv, amphibious landings in the south, encirclement of the experienced Ukrainian brigades in the Donbas, and a wide advance in the south aimed at capturing as much territory as possible.

The first phase ended with the failure of the Russian assaults on Kyiv, Odessa, and Mykolaiv, the successful Russian capture of Kherson, swathes of land in the south and in the northeast, and a general Russian retreat from Kyiv and all of Northern Ukraine.7 It resulted in the crippling of Russia’s professional army, particularly its elite units, and the Ukrainian army strengthening after the shock of the first few days. As the conflict transitioned from a lightning ‘special operation’ intended to resemble Desert Storm into a real state-to-state war, Western support coalesced behind Ukraine. Russia pulled back from Kyiv and focused on the east.

The second phase was characterized by a grinding artillery-based assault on the Donbas, mainly the extreme northeast around the twin cities of Severodonetsk and Lysychansk. As the Russians downscaled their goals steadily, the Ukrainians shifted their strategy from simple reaction and resistance to attritional warfare; Ukrainian leaders were explicit that the purpose of the Azovstal factory garrison under siege in Mariupol was to tie down and degrade Russian units as long as possible, with no hope of rescue. Whether this strategy was successful will likely only become clear years after the war ends, but one popular assessment is that this tactic of ‘corrosion’ weakened the professional Russian army enough to allow for Ukrainian counteroffensive victories in the third phase.

In August, two paired Ukrainian counteroffensives in the southern region of Kherson and the northeastern region of Kharkiv liberated thousands of square miles from Russian occupation. These offensives were dramatically successful, particularly in Kharkiv. In response, Putin illegally annexed 4 Ukrainian oblasts and enacted a partial mobilization, calling up over 300,000 soldiers; some (though not most) of these soldiers were quickly thrown into the lines with little to no training, while others underwent months of training. Eventually, the Kharkiv offensive ran out of steam, culminating just short of Kreminna and Svatove, and the lines in Kherson stabilized at the Dnieper River as the fall/winter mud season (rasputitsa) set in.

We are currently in a fourth phase, although the last two months might be retrospectively categorized as a transitional period prior to the spring campaign season (the map above has the third phase extending into late January). While reports vary, it’s probable that Russia has begun a major offensive in the east, and it’s likely that Ukraine is either not ready to launch an offensive or is waiting until an opportune moment when their readiness and integration of Western arms coincides with Russian exhaustion. Both Ukraine and Russia have spent the last two months rearming, training, and preparing for the battles to come. Major new announcements of Western military aid belie their lengthy delivery and training schedules, and the unity of both sides have shown warning signs of cracking— political scandals in Ukraine, especially within the defense ministry, and escalating factionalism between Wagner and the formal Russian military.

While the future course of this war is uncertain, the conflict will quite likely continue for the remainder of 2023 and into 2024. As far as publicly available information shows, neither side currently has the forces or equipment to effectively and decisively defeat their opponent, and likely won’t for the foreseeable future.8

Where will that leave us? That’s a question that will become clearer in the coming months.

'Semi-stable' is generalizing quite hard, please excuse my brevity. Crucial and dramatic developments after the war 'settled' (i.e., after the first two weeks) include the drive from Mykolaiv, Russian retreats from Kyiv, Kherson, and Kharkiv, and the fall of Mariupol, Severodonetsk, and Lysychansk. But it's not an overstatement to say that the war could have been won in the first week (or even the first few days), had the Russians not been stunningly stupid and overconfident. After the country did not, in fact, fall before the reaper, the war has thereafter been more 'stable' in that the sort of sweeping, rapid, lightning operations that characterized the first week became much rarer. In retrospect, there was essentialy no chance of a sudden collapse/defeat by either side anytime between late March 2022 and the present, although hindsight is 20/20.

Suffice to say, in a painfully short TL;DR, Ukraine became independent in 1991 out of the ruins of the USSR, and has tried to balance relations with the West and Russia thereafter. In 2013, then-President Yanukovych refused to sign an agreement bringing Ukraine closer to the West and the EU; this (to simplify drastically) led to the 2014 Maidan revolution, which ushered in a pro-EU government. Russia seized Crimea and fomented a rebellion in the eastern industrial Donbas region, and in doing so violated the 1994 Budapest Memorandum where Russia promised to give Ukraine territorial guarantees and security assurances in return for Ukraine handing over nukes and long-range missiles and bombers inherited from the USSR. After setbacks suffered by the two 'rebel statelets' or 'proxy republics,' the Donetsk and Luhansk Peoples' Republics, Russia forces openly entered mainland Ukraine in August 2014 and pushed Ukrainian forces back. The front line of that rebellion eventually froze more or less in place, although sporadic fighting and regular shelling continued for the next eight years. I'll likely do a couple of posts on the Maidan, the Donbas war 2014-2022, and would love to get into Ukrainian history prior to 2013, including the cradle of Russian civilization, Kyivan Rus’, if there is interest!

Luhansk and Donetsk People's Republics. Russia was the only country to have recognized their sovereignty, although they were later recognized by those paragons of international law Syria and North Korea, as well as the similar rebel statelets/breakaway regions of Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, prior to their annexation (along with Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts [provinces]) in September 2022.

Initiative is a critical factor in conventional war. It's tough to define, but easy to (retrospectively) recognize. Briefly, it's where one combatant is able to, to a degree, control where and when the fighting will focus, with freedom of action. Russia had the initiative in February and much of March 2022— they decided where they would attack, in what manner, and when. Ukraine was entirely on the defensive and could only respond/react to events as they occurred. Russia's hold on the initiative weakened thereafter as the fighting shifted eastward and their army was steadily worn down. The much-telegraphed Kherson offensive was the first time Ukraine held the operational initiative; the lightning Kharkiv offensive showed that Ukraine also had the strategic initiative by being able to more or less dictate where Russia would position the bulk of its elite troops. Now, however, those offensives are over or culminated, and it's an open question who holds the initiative; early indications are that Russia has some operational initiative.

Advantage and initiative are often correlated, but not necessarily the same; history is full of examples where the side with the initiative lost (Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg, Battle of the Bulge, plenty of sieges).

Culmination is another specific term in military studies, defined as the moment when "the remaining strength is just enough to maintain a defense," and is largely incapable of further attacks. Culmination does not mean defeat, or exhaustion (although they often go hand in hand), or even that fighting dies down— it simply means that the attacking force has no chance of victory unless the defending force unilaterally gives up. As this is a shift in relative combat power, it usually goes hand-in-hand with a shift in which side holds the initiative.

While each of these phases were bookended by relative lulls, it’s important to keep in mind that heavy fighting has been ongoing essentially at all times; the siege of Severodonetsk, which took place during the summer ‘stalemate,’ exceeded Fallujah or Basra in its intensity.

The reasons for the nearly-inexplicably terrible performance of the Russians, the so-called "second army in the world," at taking on a nation a third their size have been much discussed, and there's a lot of good analysis out there. My general read on the reasons for their failure is that many factors were at play, including Russian incompetence/ overconfidence, Ukrainian resilience/preparation/competence, Zelensky staying in Kyiv (seriously, while I'm not one to fanboy over the current media darling, this was probably critical), Ukrainian victory at Hostomel Airfield, and Western intel sharing and provision of weapons and financial support, though it's important not to overestimate how important the Western weapons are, even if we'd always like to be the main characters— about Kyiv, an advisor to Zaluzhni said "[Western] anti-tank missiles slowed the Russians down, but what killed them was our artillery. That was what broke their units." I'll write about this in a future post.

This is predicated on there not being any huge surprises, major blind spots, or black swan events. For example, we don't know much about the actual state and health of the Ukrainian economy— it is limping along, but there are plenty of examples of wartime economies imploding. Same goes for the 'true' state of Ukrainian armed forces— in Kharkiv in September, they showed that they had substantial mobile reserves (in effect, a spare army uncommitted elsewhere) that weren't publicly known, but do they still have similar reserves? Or is what they have on the front line essentially all they've got? The same goes for Russia— commentators have been prophesizing the imminent collapse of the Russian army and economy for months now, with little sign of either occurring— but that does not mean it won’t happen, potentially suddenly. And what if there was a real black swan event— a real worldwide depression, Chinese invasion of Taiwan, some other war somewhere else, another pandemic, Russian nuclear use, or Putin simply drops dead? All of these would completely change the calculus here; none of them are very predictable with publicly available information. This is why Michael Kofman's catchphrase (as much as a policy wonk would have one) is 'warfare is contingent' on thousands of factors.

An easy synopsis but it takes several articles to explain the covert 2014 Maidan and coup d;tat in Kiev in order to lay the foundation of a Russian SMO 8 years after Donbass had 50,000 dead and wounded civilians by the Kiev/Azov/Nato armies. All Kiev needed to do is give Donbas and Lugansk the same autonomous republic status as Crimea has had since the 1930s, and this all could have been Evaded. A very simple procedure, but evidently with Merkle and th French Prez. hollande spilling the beans - the plan was to create a Ukie/Nato army to get Russia to fight. Well, it worked , but Nato and certainly Ukraine will pay the ultimate price. I first started to work in Ukraine in 08 and retired in 2012 - I'm still in the same place and I'm a old Nam vet. I could also tell you about the Georgia shelling of South Ossetia in 08. Спасибо